Even if id Software didn’t invent the FPS, Wolfenstein 3D was certainly the moment the genre crossed into the mainstream. Tight gameplay, a compelling theme and the shock of such realistic graphics were critical, of course, but something else that helped Wolfenstein to reach so many players was that it was distributed as shareware.

Shareware

As hobby products, early videogames had no formal distribution network and were sold through computer stores or software clubs, usually as a disk or tape with photocopied instructions. As a result, there was a certain amount of luck involved in choosing a game; word-of-mouth recommendations were essential. Over time this evolved into more polished boxed products and magazine reviews, but people still had to pay up front for their games and hope they liked them. ‘Shareware’, a term popularised by Jay Lucas in the magazine InfoWorld, allowed people to pay for software they already had. Apogee’s Scott Miller turned this into ’the Apogee model’: providing a portion of each game for free so players could decide if they liked it and then pay for the rest (hence Wolfenstein, DOOM and the like being divided into episodes, with the first episode given away). The rise of the internet Initially distributed by floppy disk, full games arrived only after players had posted payment and waited. Shareware moved online as the internet grew, first through bulletin board systems, then FTP and the World Wide Web. Now people could download shareware directly from the developer or publisher and pay for immediate access. Of course shareware had its downsides, such as the risk of downloading a virus, and the fact that anyone could release anything, making finding good games a challenge (a problem which still affects the games industry today). But the approach was a resounding success for id, with David Kushner’s book, Masters of DOOM, reporting their first month’s royalties as $100,000 (more than triple what their biggest previous game had managed). Huge numbers of people were playing, discussing and sharing Wolfenstein, and as the buzz grew, it attracted more and more interest.

Developers and publishers

It made sense, then, for id to continue to use shareware to distribute DOOM, its sequel, and Quake, though each of their games would also see release as a boxed product through a traditional publisher. It’s worth briefly discussing game publishers here, because the vast majority of games covered in this book saw release through one. Simplifying hugely, each game has a developer – the team that creates the game – but those games are marketed and distributed through a publisher. More importantly, the publisher usually pays for the game’s development and then hopes to recoup that money through sales, meaning they have enormous power over the developer. For example, when they sign with a publisher the developer may have to hand over the rights to the IP (Intellectual Property) they’re creating, meaning the publisher now owns it. This is why you’ll see some game series abruptly change developer, with the publisher assigning subsequent games to whomever they like.

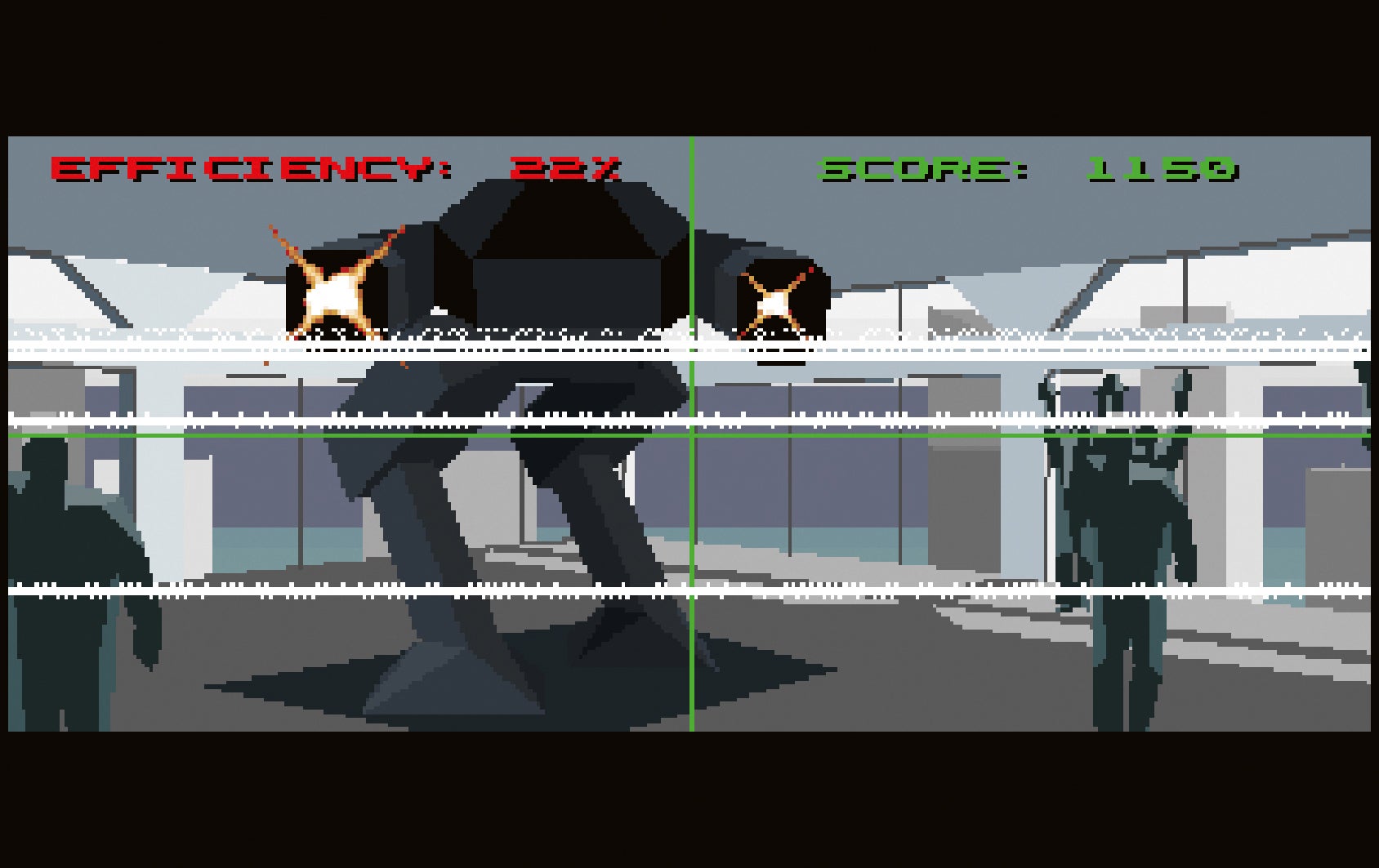

RoboCop 3

Developer: Digital Image Design Original platforms: Amiga/Atari ST/PC While most games based on the RoboCop licence were 2D platformers, Digital Image Design used a heavily modified version of their F29 Retaliator flight-simulator engine to create an entirely polygonal first-person adventure. There’s free-roaming driving, and a flying section, but by far the best parts are the FPS levels. None of its gameplay styles are developed enough to form a full game, but they make up for this with variety. As RoboCop, you search back alleys, police stations, hotels and the OCP building, with a ‘hotter/colder’ beeper that certainly raises the heart rate. One section lets you choose your enemies, potentially pitting you against several ED-209s. There’s even a first-person fight with a ninja robot in which you spam awkward punches and kicks before falling back on drawing RoboCop’s gun and shooting them. You can fire at any position on the screen, aiming near the edges to turn. With no way to strafe and the controls making it tricky to navigate corners, enemies gradually chip away at your ‘efficiency’, getting cheap shots in before you can even see them. You also need to avoid harming civilians and shoot incoming grenades, as both quickly kill you. Yes, the FPS sections are slow, abstract and clumsy, but there’s an undeniable thrill to gliding into a packed room and killing three enemies with three headshots, all without hitting a hostage.

Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss

Developer: Blue Sky Productions Original platform: PC For two games released in the same year, it’s fascinating just how diametrically opposed Ultima Underworld and Wolfenstein are. While Wolfenstein focused on speed, Underworld revolved around player freedom, and where id stripped back anything that got in the way of combat, Blue Sky kept adding features. Falling between an RPG and an FPS, Underworld was built on a bank of relatively simple gameplay systems that combined to give the game incredible depth and flexibility. The environments are 3D, letting you look up and down, swim and jump. The music is dynamic; you have an inventory and stats; you can create and cast spells, write on the map, plant a tree, bash down doors, eat and be poisoned, and lots more. The combat mixes player skill with invisible dice rolls and can get a little repetitive; it usually consists of stepping forward to attack then backing off, though it does allow you to swing, stab, chop, shoot and even throw things. There are also conversations with NPCs, complete with olde worlde English (‘Thou shouldst watch thyself’), though the game’s flexibility extends to letting you murder almost everyone and still be able to complete it. Underworld was developed by Blue Sky Productions, who would later merge with Lerner Research (best known for simulators like F-22 Interceptor) and evolve into Looking Glass Studios. The game’s engine originated from 1989’s similarly ambitious Space Rogue, but was replaced to allow for texture mapping and the last minute addition of a lighting system. There was no grand plan for Underworld or its engine, with features added over time. In an interview with PC Zone magazine, programmer Doug Church said, “We wanted to do a dungeon simulator, and none of the programmers had really done this sort of game, so we were pretty ambitious and not too smart.” Though its fans loved it, Underworld’s demands – both in its technical specs and in the dedication required from the player – made the game a slow seller, causing Origin to dial back its advertising. That said, the publisher was already struggling to explain the complex game’s premise, with one ad calling it “the first continuous-movement, 3D-dungeon, action fantasy!” Adding designers to the team for the sequel, Ultima Underworld II: Labyrinth of Worlds (rather than programmers creating all the content, as in the first game), brought more polish, colour and variety to the quest. Unfortunately, it too sold steadily but slowly, meaning Origin, and later new owners Electronic Arts, had little interest in a third game. As a result, the series would lie dormant until a spiritual sequel, Underworld Ascendant, was released in 2018. Irrespective of its sales, it’s easy to trace a line of descent between Ultima Underworld’s technical innovations and freeform ethos, and later immersive FPSs like System Shock and Deus Ex. PC Gamer’s Tony Ellis summed it up nicely with: “Wonderfully, richly, impossibly interactive, UUII was a game from the future.”

Wolfenstein 3D

Developer: id Software Original platform: PC In 1992, id (originally Ideas from the Deep, later shortened) was best known for its shareware-distributed 2D platformers following the adventures of Commander Keen. But behind the scenes, John Carmack – id’s engine programmer – was working on convincing the slow PCs of the day to draw first-person mazes. These initial experiments – Hovertank and Catacomb 3-D – incrementally built towards the game which would blow id’s previous successes out of the water and set its direction for the next three decades: Wolfenstein 3D. Playing as BJ Blazkowicz, you explore the dungeons and corridors of Castle Wolfenstein, mowing down Nazi soldiers, dogs and over the top bosses, including the infamous Hitler-in-a-robot-suit. Even today the prominent swastika flags and DeathCam™ showing each boss’ graphic demise still raise an eyebrow, though id weren’t asked to tone down the gore until the Super Nintendo conversion (more on this when discussing 1994’s Super 3D Noah’s Ark). Wolfenstein’s setting is based on Silas Warner’s 1981 Apple II stealth game, Castle Wolfenstein, which id bought the rights to, and despite the speed of the player’s movement Wolfenstein 3D still retains the ‘feel’ of a stealth game. Enemies deal huge amounts of damage, so charging into rooms means death, though the generous auto-aim and high damage you kick out dispatch foes just as quickly. This gives the game a stop-start rhythm of cautious firefights and racing through labyrinthine corridors. The feeling of being in a maze is reinforced by the lack of roof texture, meaning it always feels vaguely outdoorsy. From a modern perspective, Wolfenstein 3D’s limitations are clear, though each of them clearly originates from the focus on speed: in order to get the player’s movement smooth and fast the engine has no lighting, angled walls or variation in floor height. Plus, to focus the gameplay on exploration and combat, id stripped out proposed features like searching or dragging dead bodies. The result, particularly in later episodes, wavers between attempting to provide immersive castle environments and Pac-Man style mazes (to the extent that a level paying homage to Pac-Man’s maze was hidden in the game). Compared to later FPSs, Wolfenstein 3D’s gameplay incorporates arcade-like elements such as the player having lives, an approach that would quickly be dropped for the more modern save/load system. Kills, speed and collecting the treasures hidden in the castle’s many secret chambers earn you extra lives, and if you lose one you restart the current level with your weapons reset. Though the game’s technology and gameplay are both limited, it’s easy to see how incredibly immersive Wolfenstein 3D must have been to players used to turn-based dungeon exploration during which enemies politely awaited their turns. Here, the environment constantly feels dangerous, and it comes as a shock when you first realise that enemies can open doors and patrol the levels. Even so, id were really only getting warmed up …

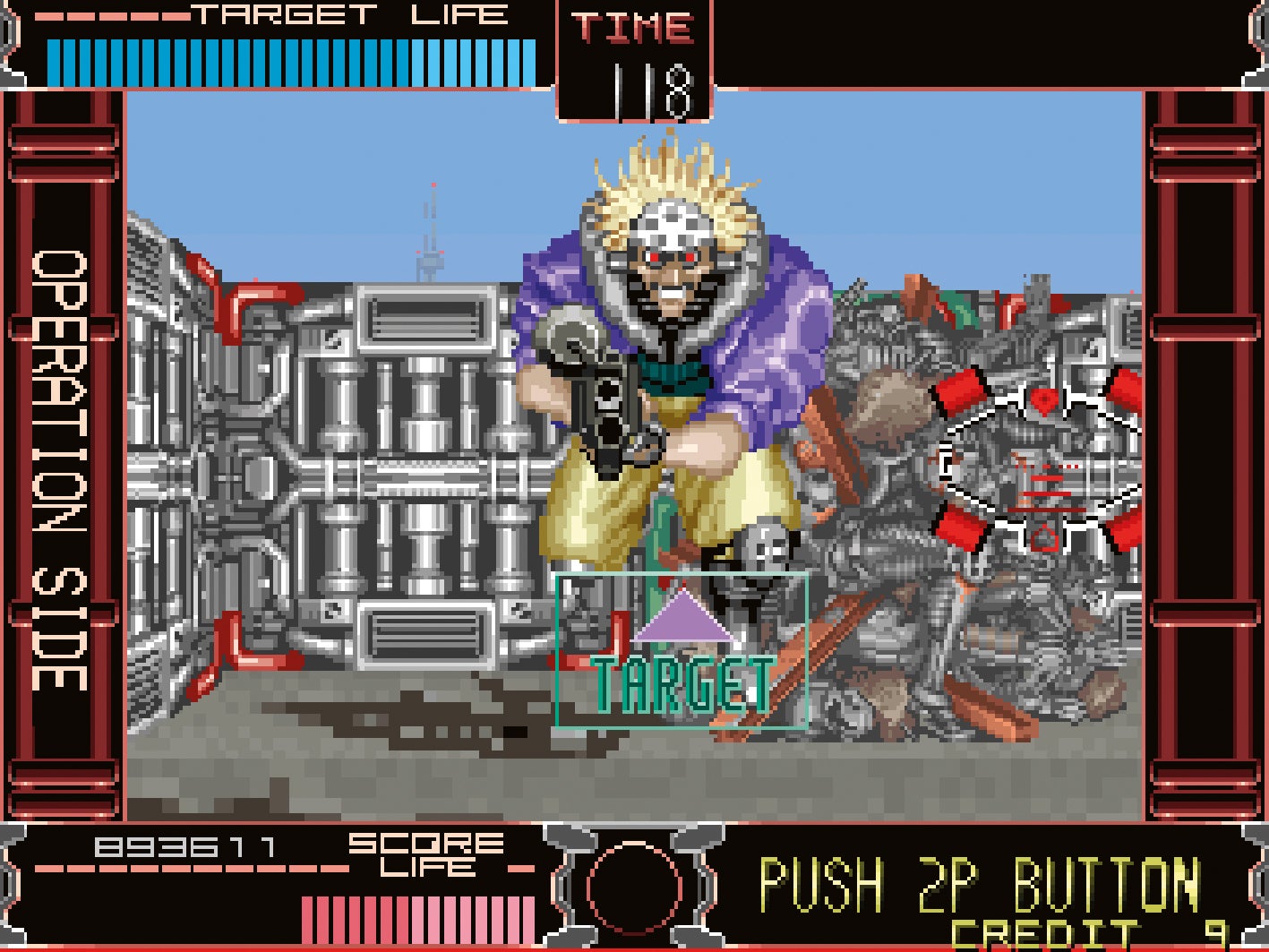

Gun Buster

Developer: Taito Original platform: Arcade Gun Buster (a.k.a. Operation Gunbuster) is a fantastic demonstration of the sheer imagination and verve of the early ‘90s Japanese arcade scene. While it includes features that wouldn’t be common in home FPSs for some years – glass, rain, co-op play – the game’s most notable feature is its control scheme. Up to four players can crowd round the huge cabinet, each using a joystick to move and strafe while simultaneously holding a gun that not only aims the crosshair but turns your view. Levels are little more than claustrophobic arenas filled with pillars to hide behind and sprite furniture to be smashed by gunfire. Combat is similarly intense, pitting you against a series of robotic bosses that could easily have stalked from the pages of any of Masamune Shirow’s manga. As if the complex controls weren’t tricky enough, the action is relentless, with bullets flying everywhere, constant explosions, small enemies being spawned that fire smaller missiles and even characters who suddenly appear at the front of the screen to stab you. Also of note is that in contrast to Wolfenstein 3D’s ‘hitscan’ enemy shots, which either instantly hit or miss, here some projectiles must be shot down while others need to be dodged. While it’s no surprise that the challenging pat-your-head-while-rubbing-your-tummy controls made Gun Buster an intimidating arcade game, it’s nonetheless a fascinating glimpse at an evolutionary path the FPS could have taken. Thanks to Bitmap Books for the excerpt - you can buy I’m Too Young To Die from Bitmap Books’ own store.