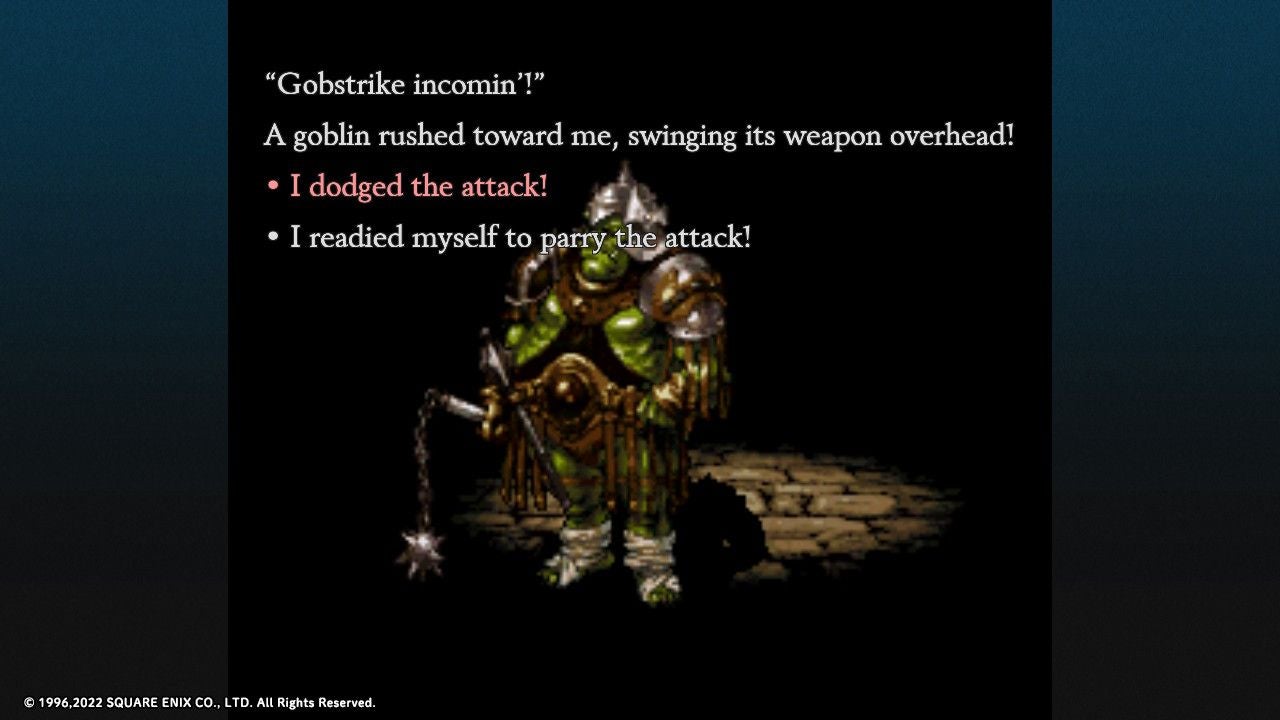

This journey sees you warping back and forth between worlds, the basis for a narrative in which every character, place or thing is haunted by its alternative. In one reality, a vast technological complex exists far across the sea; in another, it is a ruin. In one reality, a local man has become an accomplished fisherman; in the other, he is a feverish recluse who worships a straw idol (which you can eventually recruit as a party member). In one reality, the lagoons surrounding a fairy village have been drained, thwarting access to a dragon; in the other, they have been overrun by goblins ousted from their homelands. Where its acclaimed SNES predecessor Chrono Trigger operates period by period, Chrono Cross offers a universe without a past: everything that might have been exists simultaneously, giving rise to a pervasive anxiety as possibilities clash and threaten to cancel each other, a predicament emblematised by the game’s omnipresent, beautiful but horrifying ocean. This applies especially to Serge, walking the boundary between life and death, existence and anachronism - an irresolution that feeds into one of the greatest plot twists of the PS1 era. But Serge is also a kind of cosmic janitor, switching dimensions in order both to bypass obstacles and reconcile the tensions between parallel selves, each the ghost in the other’s mirror. Lest all of this sound offputtingly conceptual or just plain old depressing, know that Cross is at heart a jolly save-the-world adventure that alternates poignancy with absurdity. Just look at its 45 playable characters, some of whom can only be recruited during your second playthrough: strutting J-pop idols and hags who mimic previously defeated monsters; moody boy painters and jesters who speak Monty Python French; a skeletal clown you’ll slowly assemble bone by bone. Switched into your three-strong party at savepoints or on the overworld map, these unlikely allies are distinguished both by their stats, and by configurable grids into which you’ll slot spells - “Elements”, as they’re known here - and unique Tech abilities. All have personal dramas to uncover that stretch between realities, though the size of the cast means that only a handful receive the depth of attention you’d associate with party members in the PS1 Final Fantasies. The main story is thrilling, striking a balance between the conciseness of SNES-era text boxes and the lavish monologues of later 3D RPGs. It takes you to some eldritch places. There are tower dungeons with puzzles that involve changing the party order, shimmering flooded forests and chaos dimensions in which paths weave together Escher-style. As in Trigger, enemies are visible on area maps and can be avoided, which makes those pre-boss dungeon runs a little less arduous than in Final Fantasy. Cross is also relatively light on grinding. Rather than gaining XP and levels from regular battles, you earn useful, but not essential boosts. Major story battles earn you something like a traditional level-up, with stat increases picked for you according to background variables; these are applied to every recruitable character in the game, rather than just the active party, so feel free to favour or neglect companions as you please. The remaster accentuates this unintuitive but flexible approach to progression by letting you turn off regular encounters entirely, though you’ll sometimes need to fight creatures anyway because they’re blocking an entrance (and power-ups aside, you’ll want to do a bit of extended monster-mashing here and there for the sake of new spells and equipment-crafting materials). You can also automate physical attacks in battles when harvesting crafting materials, regaining control with a click of the stick. Combat itself is perhaps Chrono Cross’s strangest element, for all its superficial resemblance to the separately loading, party-based battling of Final Fantasy. It’s worth digging into this aspect at length, because I still struggle to make head or tail of it myself. Rather than predictable turns or the cooldown bars of Active Time Battle, the proceedings are governed by an invisible clock. Physical attacks - grouped into light, medium or strong, in order of decreasing accuracy - and spells or “Elements” advance the clock, with enemies attacking after a certain number of ticks. Attacks and spells also deplete your stamina, with a maximum of seven stamina points per character. You can perform actions with each character as long as they have stamina, mixing and matching attacks and elements, and even switching between team mates. Elements, however, always cost seven stamina points and so generally leave you with a deficit, which must be paid off before they can act again. It’s best not to drain everybody’s stamina in one fell swoop by spamming Elements, because if everybody’s in debt to the clock, the game will skip forward and bring about enemy turns more frequently. So how do you keep your party in the black? Well, when characters attack or cast Elements they also replenish the stamina of their allies, as though giving them a bit of breathing space. So, if one character has negative stamina, you can coax them back into action by having another perform a string of attacks. Battles thus become feats of juggling, emptying out one character’s stamina, then switching to another to refill their tank, though it’s not an equal transaction of action for stamina point, so you can’t just shuffle stamina back and forth indefinitely. With me so far? There’s more. Physical attacks are also how you access each character’s spells or Elements, increasing the active character’s Element level by variable amounts and so, opening up higher tiers on their Element grid. So in addition to juggling stamina, you’re thinking about whether you can level up a character and fire off an Element before the enemy responds. As you can hopefully tell, uncertainty about the running order is the critical ingredient here: do you have time to raise the Element level of a character equipped with a juicy top-tier spell, or should you prioritise lower-level healing Elements in case the enemy is prepping a showpiece move of their own? We’re not finished yet. There’s also the question of Element affinities – fire/water, light/dark, air/earth. Characters have an innate affinity, which makes them better at using, and more resilient against Elements of the same affinity. But Element usage also slowly alters the affinity of the battlefield itself, represented as three concentric circles in the top left, which in turn, enhances Elements of the same affinity. So in addition to juggling stamina points and Element-levelling, you’re also engaged in a tug-of-war with your adversaries over the terrain chemistry, striving to sway the surrounding synergy your way so that potentially match-ending spells do the maximum damage. It’s a lot to process, and Chrono Cross isn’t always brilliant at explaining itself. There’s a series of comedy tutorial battles early on but certain variables, like what status effects actually do, remain unclear. More importantly, the game doesn’t really pressure you to understand and master the workings of stamina, Elements and affinities till you’re a fair way in - around the 15-20 hour mark, for me. It’s an acquired taste, even at its best. Much as I enjoy guesstimating enemy attack tempos, I also miss the visible timelines of games like Final Fantasy X and the recent Othercide, which trade suspense for the ability to plan. It can be hard to know in Chrono Cross whether your calculations are paying off, thanks again to the overly gentle challenge curve; often, Element levels and stamina feel like pointless contrivances. But if Chrono Cross’s battle system is murky, it can be brilliant when things do come together in the shape of later bosses, where gauging openings and tuning affinities is the difference between a close victory and a party-wipe. Pulling back from the nitty-gritty, combat is also an enjoyable restatement of the game’s themes. Much as the story explores parallel histories that are obscurely interdependent, so the battle system treats time as a thing thrashed out between opposing parties, with units of agency passed back and forth. This is one of Square Enix’s more dutiful visual restorations, with character models given a handsome make-over while pixelated backdrops are largely left to wither in the glare of today’s HD displays (in fairness, there’s a choice of Classic or Enhanced modes at start-up, with Enhanced rounding off those background pixels). The frame-rate during combat is as uneven as it was in 1996. The convenience of skipping encounters aside, the remaster’s silver bullet is the inclusion of the Radical Dreamers visual novel, another quasi-sequel to Chrono Trigger featuring Serge and Kid, originally published for the Satellaview. Beginning with a mansion heist, it’s an elaborate but snappy yarn, enjoyable both in itself and for how it contrasts or complements the events and structures of the RPGs: there’s something resembling a battle system, for instance, but choices such as attack or defend are narrative branches. One elementary thing I relished about the writing was that, as confusing as it may sound to explore a labyrinth of traps and locked doors in text-based form, I never got lost: descriptions update to reflect the fact that you’ve already visited an area. Cross often feels like a visitor from a parallel dimension itself - sequel to an acclaimed RPG that’s in practice more of a companion piece, reminiscent of the PS1 Final Fantasies but a very different beast on the battlefield. It’s an engrossing epic, mixing sadness, whimsy and a touch of cosmic dread without, somehow, disintegrating into farce, and if the battle system can be a touch infuriating, coming to terms with it is part of the adventure. The remaster isn’t a dazzling effort, but the game’s revival in any form is something to celebrate. I am eager to read reactions to it from players who got into RPGs after the Chrono series went under.