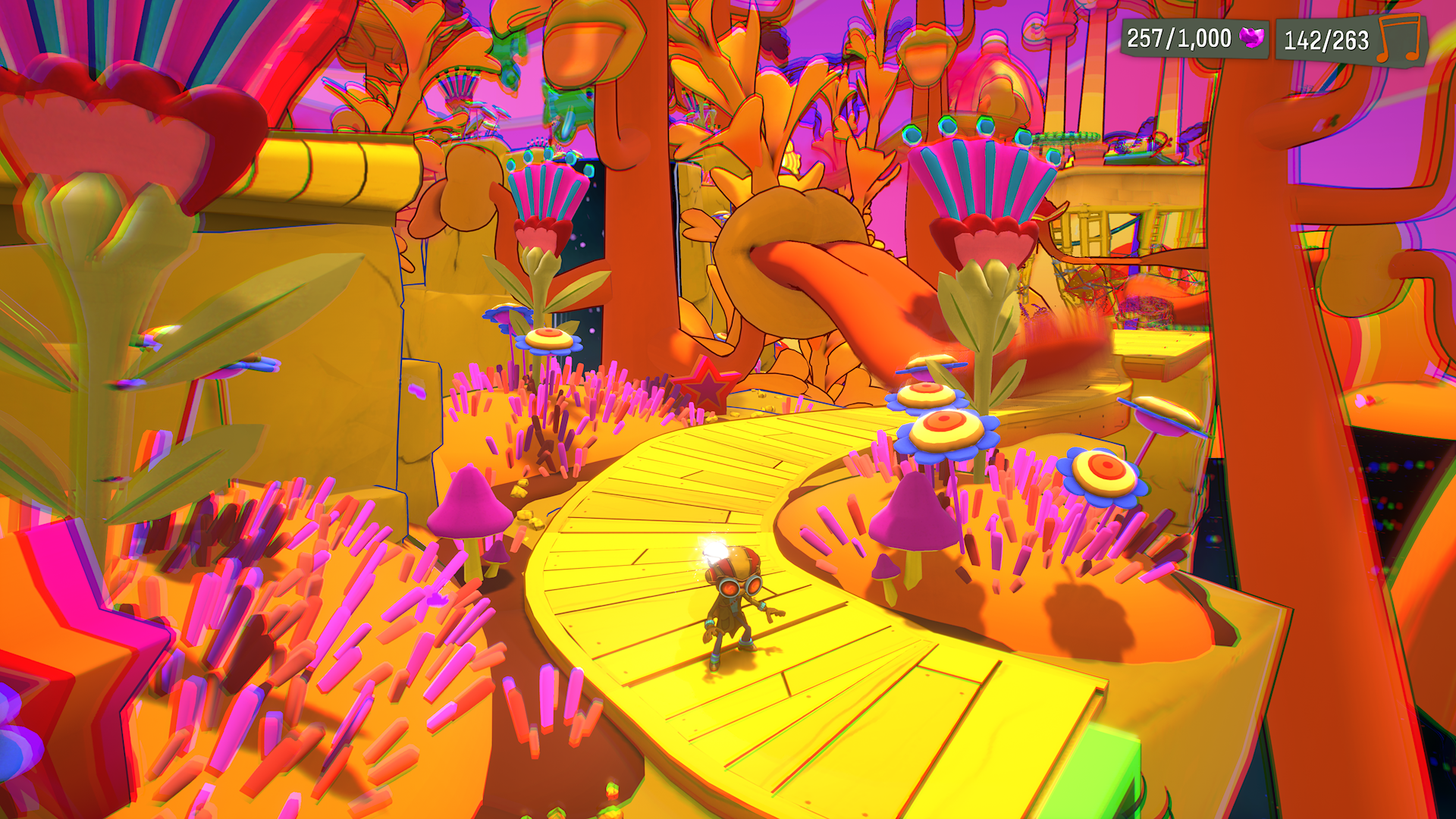

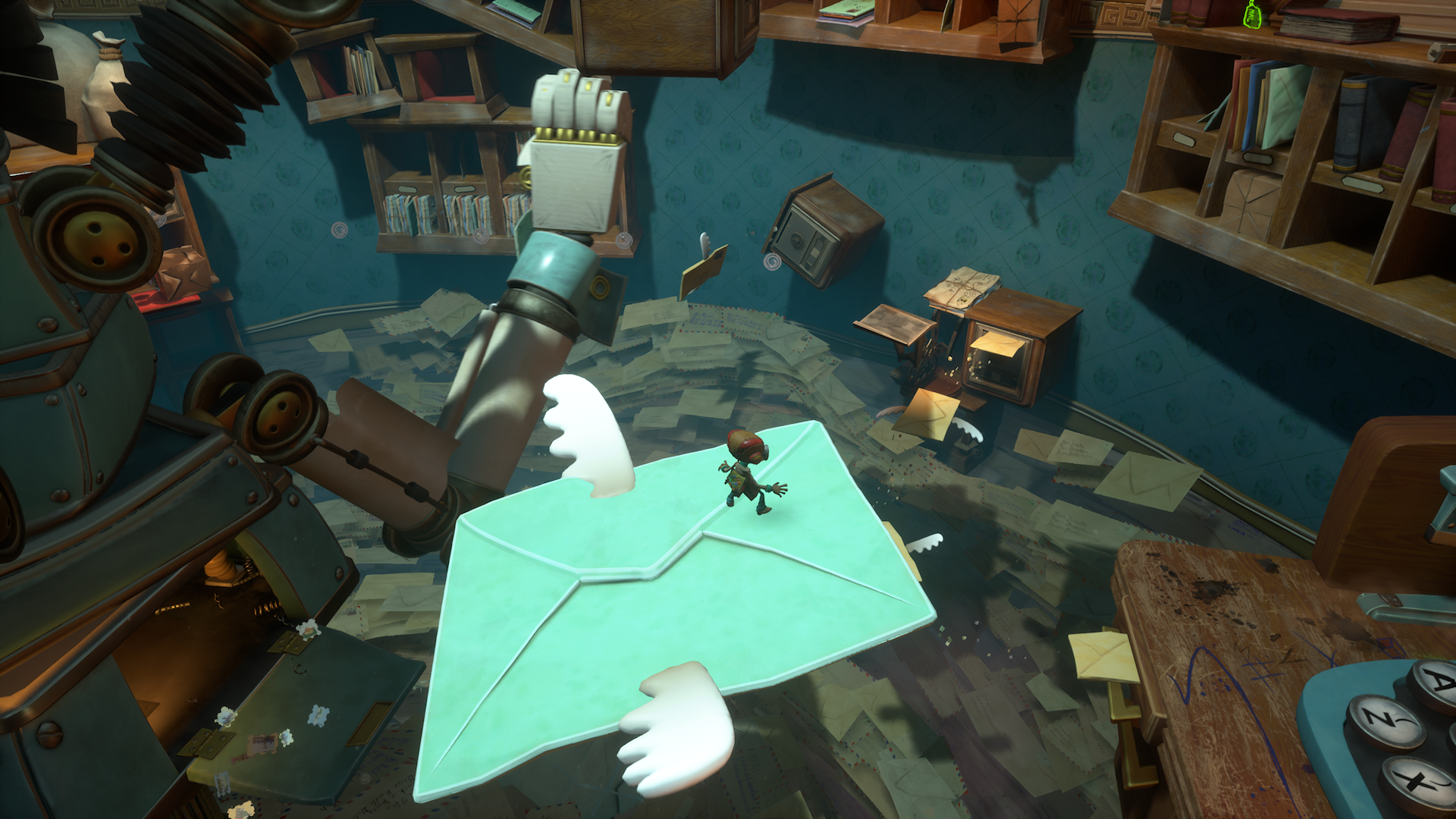

Rolling and bouncing around those brilliant stages, messing with Sasha’s tightly-wound neural plumbing and visiting the house fire inside Milla’s cerebral disco, I thought of how my own teachers had, in various ways, opened their minds to me, suffered my trampling questions and generally made themselves vulnerable so that I could learn. I don’t want to suggest that this is everybody’s experience of teaching, or being taught, or that there’s no place in teaching for boundaries. But it’s surely the kind of connection every teacher hopes to create, and plenty of game developers, too: here is the world of my experience. Spend time with me here and see what you can bring away. Having learned from these worlds, you’re then in a position to restore them, helping the owner confront their personal demons and unpack buried truths. It’s an idea carried forward into Psychonauts 2 - the same clever and caring game, but slicker, busier and with updated notions of mental health that reflect, not least, the crunch and burn-out of the original’s development. Psychonauts 2 begins just after the events of VR expandalone Rhombus of Ruin, with circus acrobat turned mind-diver Razputin Aquato joining the intern programme at Psychonauts HQ - an Epcot Centre-style hub where you’ll find brains in hamster balls and a man haunted by visions of flying bacon. The first thing you do is hack the memories of one Dr Loboto, a character from the original who has links to a legendary psychic megavillain from decades past. The plot is about investigating said megavillain - who, shocker, may be more than a memory - and her relationship to the original founders of the Psychonauts, a collection of traumatised hippy Avengers whose brainscapes are all badly in need of a visit from the janitor. The Motherlobe and the forests, mine shafts and swamps that surround it are the game’s overworld, a winding and plunging expanse of bounce pads, rope swings, rails, ladders, collapsing platforms, secondary fetchquests and dozens upon dozens of collectibles. The ‘dungeons’ are the minds of the people you’ll meet, which you must probe and revitalise to glean clues about your ultimate adversary. Milla, Sasha, Oleander, Ford Crueller and Raz’s off-and-on girlfriend Lili return from the original game; new arrivals include a gang of bullying fellow interns and Raz’s circus siblings, all raised to fear psychics and as such, not entirely trusting of their wayward brother. The writing is more sweet and dry than laugh-out-loud funny, but there are some wonderful sketches: the intern making pancakes with the aid of some terrified forest creatures (“I CAN HEAR YOU ROLLING YOUR EYES, MRS THATCHER”), splitscreen heist sequences, and any scene featuring Raz’s sugary-savage mother Donatella. Raz himself is much the same scrawny yet resourceful 10-year-old as before: the butt of many jokes, touchingly naïve at times, older than his years at others. He’s still a talented acrobat, with cleaned-up platforming controls that, nonetheless, probably won’t keep Mario awake at night, and he has all his old psychic abilities: telekinesis, mind bullets, pyrokinesis, a clairvoyance skill that lets him turn other characters into CCTV cameras, and the ability to funnel his brainwaves into a bouncy balloon that can be run on for speed or dangled from to glide. The old progression system is back too, warts and all. Skills, equipped in sets of four, are upgraded by plugging psy-cards into eyeballs to generate points for your intern card. It’s still a weirdly roundabout way of doing level-ups, almost redolent of Destiny’s preposterous currencies, and it’s just the tip of the iceberg. Psychonauts 2 is an absolute quagmire of dropped tat: psitanium shards with which to buy consumables and “pins” that modify your abilities, “insight” statuettes for additional level-up points, and “half-a-minds” that can be paired to increase your max health. It carries the weight gracefully, however, because most of the collectibles plug into a joke or complement their surroundings in some way - be it a piece of emotional baggage beaming at being united with the appropriate luggage tag, or the use of “figments of the imagination” to flesh out levels with drifting themed doodles of germs, tombstones and cats. It sometimes feels like Psychonauts 2 fancies its chances at being a Devil May Cry-style combat style builder. The upgrade options include extra combo hits, ground-pounds, health leaching, dodge attacks and projectile mods. While spruced-up with a new auto-lock, the base combat isn’t really tight or involving enough to justify all the appendages, and in any case, 3D platformers like this are typically better when your abilities are left crisp and unblurred. The tactics are seldom more demanding than targeting an enemy with the right skill, and it’s a chore to keep opening the ability wheel to switch things up during multiple-wave encounters. The mindscapes more than make up for it, however. The thrill of Psychonauts 2 is partly that it’s a return to the concept of level-based worlds, which nowadays feel like an endangered species - squeezed out by an industry-wide contempt for interruptions of any kind that owes something to virtuoso “no-cuts” auteurism and something to the modern cult of engagement and monetisation. Double Fine’s choice of mental over physical geography allows it to sidestep all that without trying to. Of course there are breaks in the flow: skulls are thick, minds vary, and who amongst us really thinks in one world all the time? Playing Psychonauts 2 is like opening a series of presents. There are hints of the old platforming staples such as ice and lava, but most levels are delightful originals that put a gentle spin on the fundamentals of hopping and blasting. One brain harbours a full-blown 90s cooking show with some of the best-observed musical pastiche I’ve encountered in a game, featuring monstrous handpuppet judges and an audience of ecstatic meat and veg who must be prepped against the clock. Another houses a rock concert dressed in Sergeant Pepper hues, with rainbow bridges winding from prisms over a shimmering lake of stars, and a “Feelmobile” ferrying you between main stage and camping grounds. All of these spaces hide other spaces. Giant bottles on the tropical shores of a Mario Galaxy-esque potted planet are portals to an iridescent swamp of yellows and violets, where belching seedpod heads blow convenient craters in the scum. Another city level is set inside an extremely unsanitary bowling shoe, where germs in trilbies await the coming of the dreaded Spray-pocalypse. There are nods to other games like Super Monkey Ball, though nothing quite as inspired as the first game’s riff on tabletop wargaming, and bosses - added thanks to Double Fine’s mid-development partnership with Microsoft - that are stupendous of conceit if slightly rickety in execution. These worlds are more than parodies. Psychonauts 2 might play fast and loose with conventions and references, but its micro-realities have substance. It’s all about consistency and follow-through: if you are going to play through a character’s backstory in the form of a theme park ride, you need to have disenchanted staff taking tickets, gantries overhead where stencilled handymen peer down with cigarettes, and a control room where Lili can yell instructions through a mic. Each inner world has a slice-of-life ambience redolent of Pixar, with NPCs pursuing their own little stories in the corners - circus fleas arguing about whose turn it is on the trapeze, rattling animatronic clerks getting all steamed up about misaddressed mail, and a dragon trying to talk down a knight in shining armour. All this was true of the original game. But where Psychonauts 2 stands apart is in the careful line it walks between caricature and empathy, between treating neurological foibles as quirks and applying a more sophisticated understanding of concepts like anxiety, addiction and post-traumatic stress. The game’s opening screen forewarns you that it’s a work of fantasy, but its levels and writing are shaped nonetheless by a sense of responsibility built around consultation with organisations such as Take This. Raz, for example, usually asks for permission to enter somebody’s mind, though this obviously isn’t always possible where villains are concerned. Part of that ethic of responsibility is recognising that an action-platformer template may not be the best vehicle for what are essentially acts of invasive therapy (or, when it comes to hostile characters, sanitised interrogations). This comes across especially in certain new tools and enemies. One of the new additions is a grapple that is presented as forming “mental connections” between grey thought spirals, linking up concepts with dotted lines. On getting hold of this, Raz promptly uses it to tamper with somebody’s mind to disastrous effect, transforming their inner universe into a tortured blend of hospital and casino. It’s an opening, welcome acknowledgement that to portray somebody’s psyche as an obstacle course carries the potential for abuse. The expanded enemy line-up, meanwhile, hovers intriguingly on the edge of a Serious Games-style recreation of debilitating mental phenomena. At the sillier end of the scale you get Judges with over-sized gavels; Doubts, which bog you down; and Bad Moods that drift around hurling expletives till you use Clairvoyance to see through their eyes and track down the caged heart that will restore their good humour. But you also get fairly full-on recreations of panic attacks, manifest here as polychromatic monsters that teleport around spitting darts till snared in a bubble of slow-mo. The first time you encounter these creatures, it’s inside the mind of somebody who is dealing with feelings of sensory overwhelm and dissociation. Enablers, meanwhile, are goblin cheerleaders that make other cognitive fauna invincible. I never felt that Psychonauts took any damaging liberties with these portrayals, but there is definitely a tension between Double Fine’s continuing debts to various gothic clichés and the second game’s more sober awareness of things like consent and gaslighting. There’s an awkward moment when Agent Nein takes Raz aside to lecture him about the aforesaid act of wanton rewiring - while simultaneously handing him the ability to re-enter any brain he’s visited where he has “unfinished business”. Here, the platform game collect-a-thon element wins out over the story the game wants to tell. The same seems true of the last level, which hints at the ethic of dawning self-knowledge and acceptance that characterise most previous levels, but ends with you booting somebody’s oversized vindictive streak into a big old pit of repression - because every platformer needs its final boss. I’m not sure these are entirely criticisms, however. For me, watching Double Fine pick its way through this messy web of cliché and insight, imperfectly translating very complex phenomena into architecture, opponents and abilities, is part of the appeal. Psychonauts 2 is, once again, a universe of damaged teachers and teaching environments, a space for thinking through dark thoughts with varying degrees of earnestness and absurdity. Its worlds are works of matchless invention, its characters a joy to exist alongside. I might have missed it first time round, but I’m glad that games like this are still being made.