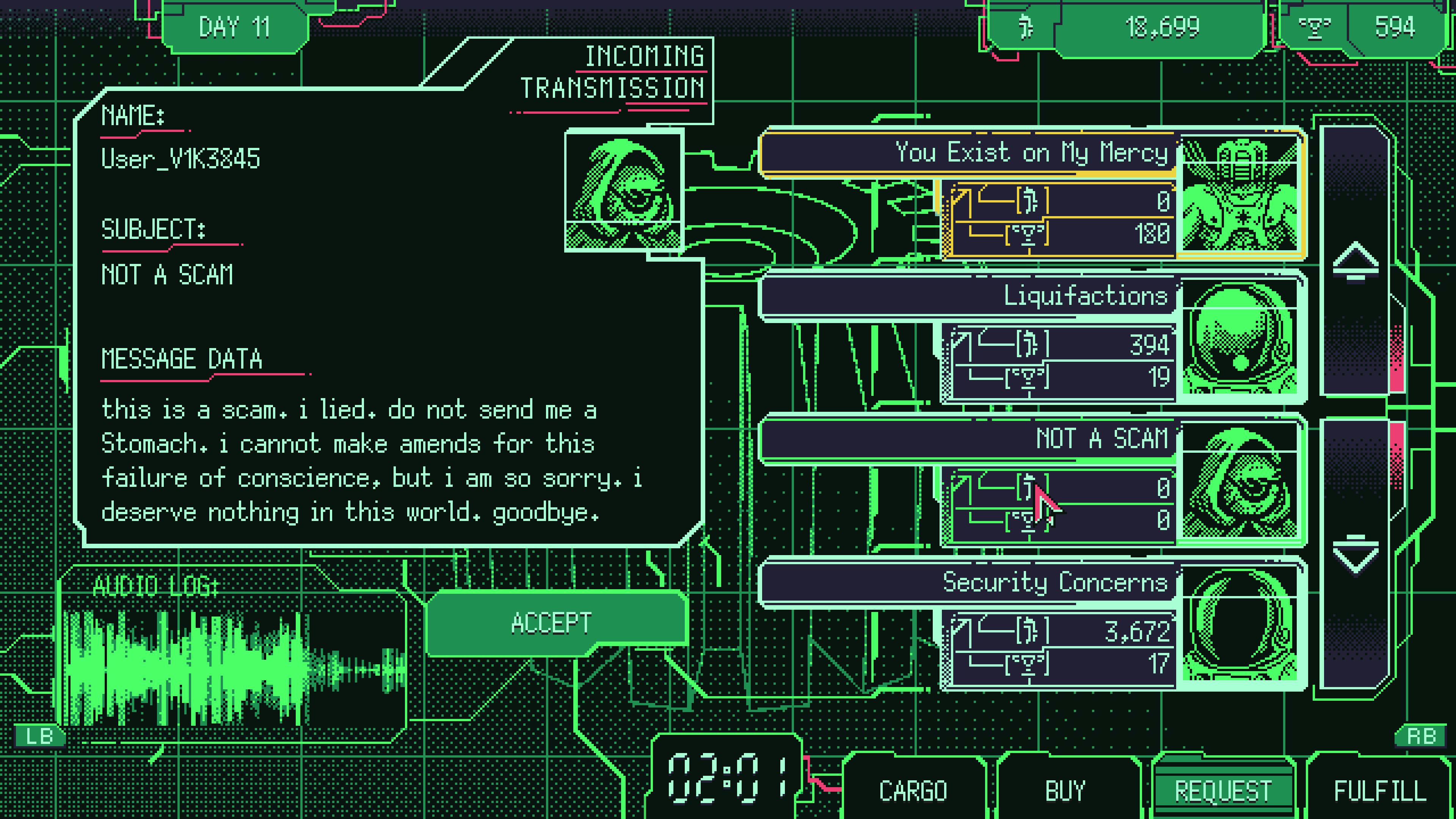

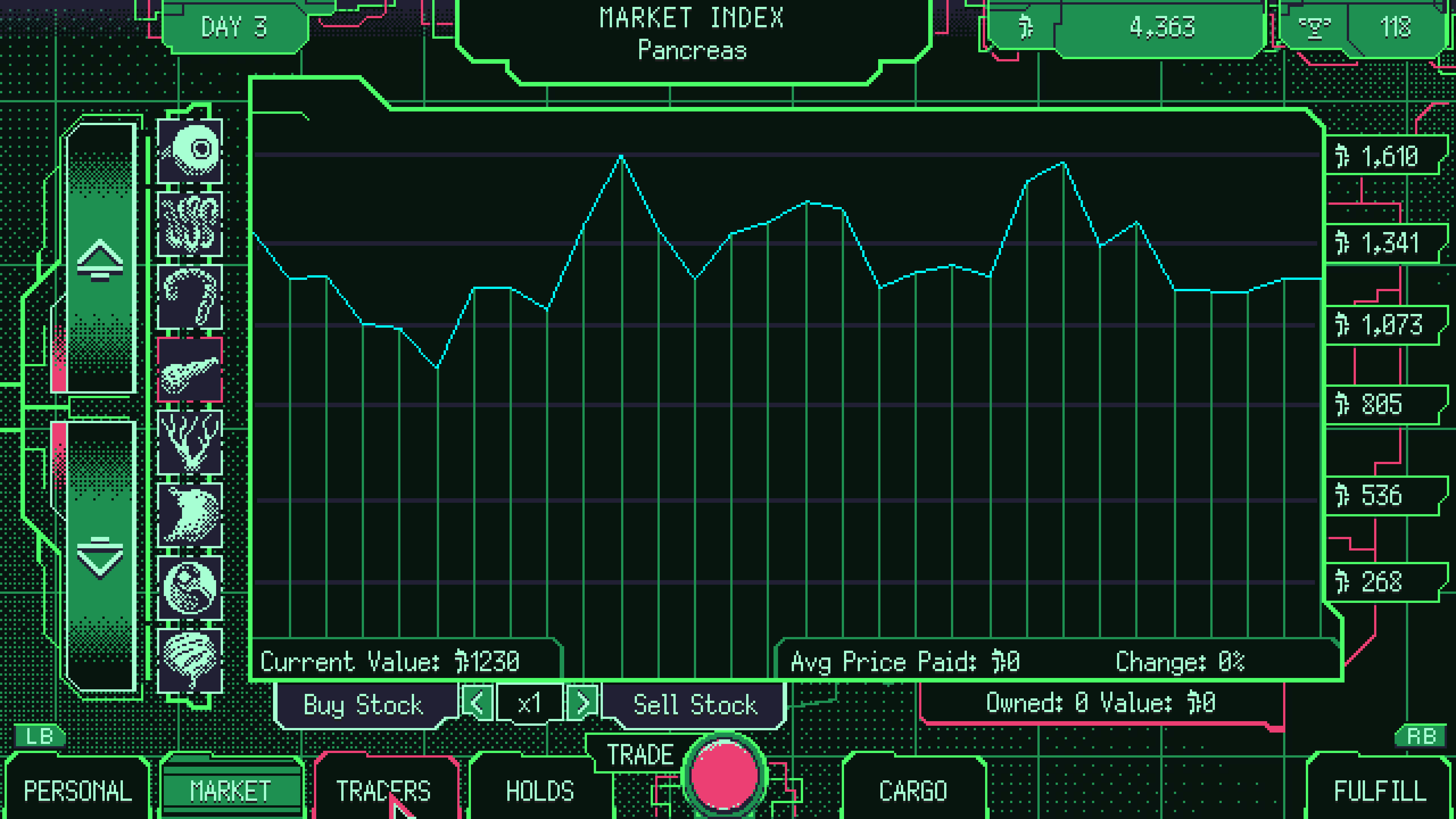

Is it possible for a soundtrack to smell? If so, this one stinks of Adderall, formaldehyde, stale pizza and several vintages of sweat, plus various other aromas that haven’t been invented or discovered yet, and hopefully never will. No, I won’t link to a Youtube video. You don’t want this stuff in your play history. There’s no getting away from the score, but you’re safest in your ship’s cargo hold: here, the backing track becomes a sort of echoey, mournful lilt, suggesting long, lonely weeks at the helm with naught but frozen kidneys for company. Switch to the stock market tab and the beat levels up into something itchy and fuzzy and ribald and obscene, spiking your heartrate, tickling your flight reflexes. Worst of all, though, is the motif that plays when you hit the Trade button and kick off another day in the offworld flesh bazaars: a brazen, rising riff, Zelda’s treasure chest music on Satan’s synthesiser. Good luck and good hunting, interstellar peddler of viscera! The galaxy is your gall bladder. Do you have the guts and vision to make a million credits? If not, don’t worry - hearts and lungs will do the job just as efficiently. It’s a simple-enough sim, for all the anatomical detail: accept requests from the buyer tab, some of which are time-sensitive; buy organs from the marketplace feed; hand them over via the fulfil tab. Each trading day lasts two minutes, and you can’t size up the offerings in advance, so you’ll need to be quick. The biggest headache is that marketplace feed. Organs of varying rarity, freshness and size are constantly being added to it, and they are constantly being scooped up by rival traders with their own specialities and levels of decisiveness or dexterity. You’ll also have to worry about having enough space in your hold, where organs slowly rot and depreciate; some of the nonhuman varieties leak corrosive fluids, robbing you of a slot till you fork out for repairs. You can buy larger hulls, including ships with freezers to keep those bundles of nerve clusters extra-crispy. But in the short term, you might want to avail yourself of the restorative powers of human souls, which increase the condition of any organ directly adjacent. That human souls are classed as organs is everything you need to know before playing SWOTS, really. The more you trade, the higher your reputation, which slowly unlocks more valuable, non-human organs for trading. The higher your reputation, the more you start to ignore individual buyers in favour of nurturing and selling organs over the stock market. You can buy stocks in specific organs: prices are affected by what you do in each trading day, but they can also be skewed by random narrative events, such as the unexpected arrival of a charnelship’s worth of eyeballs. More exotic types of flesh require more careful handling. Some organs eat other organs, for instance. Try not to leave them in storage for long. Your competitors do their best to ruin things for you; you can read their profiles on the Traders tab before starting each day. The one every SWOTS player hates is Chad Shakespeare, a grinning canine tycoon with a vulture’s eye for a Mythic liver. Your loathing for him stems partly from knowing that he has cash to burn and treats the whole thing as sport, though this is perhaps taking the characterisation more seriously than I should. But your greatest adversary is the interface, which is carefully and calculatedly unfit for purpose. Lead developer Xalavier Nelson Junior has posted at length about the art of building game experiences around friction and abrasiveness. In that regard, SWOTS is a masterclass. The organ feed is a rollercoaster of frustration, a scrolling anxiety attack befitting the obscenity of your vocation. It’s routine to accidentally buy the wrong item because the feed has refreshed between scrolling to something and clicking on it. It’s routine for another trader to snipe a high-value organ right out from under your thumb (you can, at least, see which items they’re inspecting). I often forgot that I didn’t have room for more produce and frittered away seconds clicking madly on unresponsive purchase buttons. It’s impossible to view the marketplace, your cargo hold and the requests screen simultaneously, which creates further bubbling panic as you skim-read garbled communiques and arrange stomachs for optimal conditioning, always conscious that premium meat may be squelching through your fingers. So you look for ways to speed up your reactions, instead - deciphering organ barcodes, for example, rather than wasting time hitting the “inspect” button. You also learn to cheat, paying other traders to take the day off when you need more time to think. In amongst all this mayhem, a story with multiple endings is advanced by taking on gold-framed commissions. The cosmos introduces itself gradually. There is talk of a never-ending war: many of your regulars are soldiers on the frontlines. There are pop-up scams - a strange relief, inasmuch as time pauses while you’re reading them - and predatory mentor figures. There are opportunities to Be Good, at least on the face of it: one, penniless buyer needs materials for an organ cloning farm that might conceivably put you out of business. Your character also has a Dark Past, though I imagine this is true of most people who sell xenomorph giblets for a living. Some of your buyers know about it. You can bribe them to keep quiet, or see what lurks further down the maggot hole. Providing, that is, you can find a moment to join up plot threads while jostling with Chad Shakespeare. Essential to enjoying SWOTS, to cut a long intestine short, is understanding that you aren’t really meant to enjoy the game, or even get particularly good at it. Selling organs is a vicious business, would you believe, and this isn’t one of those satires of capitalism that turns a macabre reality into a guilty pleasure. It’s a brilliantly unpleasant work, both in what it asks you to do and how it forces you to do it. The writing can be very funny, when you’re allowed to digest it: the progress screen tallies your playtime by the number of breaths you’ve taken, for instance, prompting deeply unwelcome reflection about your own, palpitating corpse-to-be. But the humour is unsmiling, spliced with frenzy, and grounded by a sense that everybody and every body in this flyblown universe is beyond redemption. It’s possible to get hooked, to master the stock market and watch the credits roll in, but always with an overriding awareness that you are doing yourself harm.