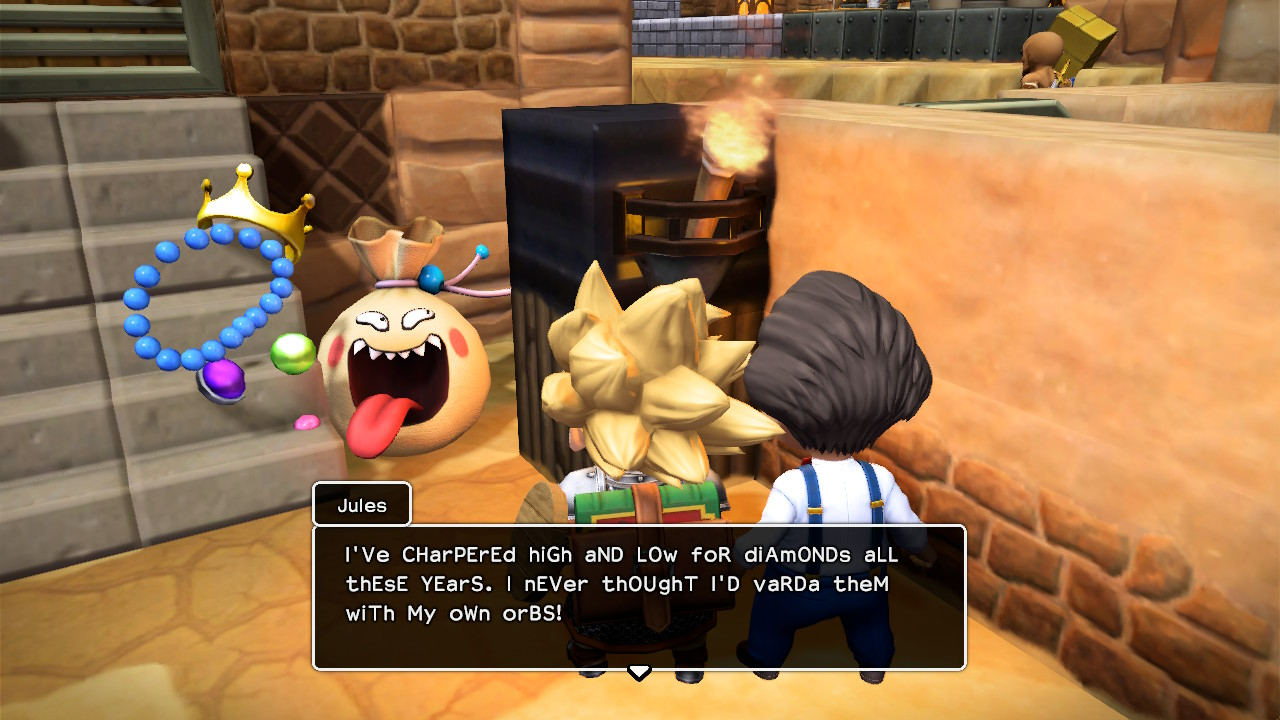

The English translation in Builders 2 is sublime. It’s a non-stop barrage of flawless puns, knockout one-liners and perfectly pitched pop culture references. It’s also a song to British linguistic diversity. The game is split into several acts. Each has its own island sandbox to play around in, its own story, and its own cast of characters who, in true Dragon Quest style, speak their own UK dialects. There’s very little voice acting and, as dialects are tricky to recognise when they’re written down, meeting a new character becomes a game of ‘guess the accent’. ‘Oo are ’ee, anyway? And what’re ’ee doing all the way out ’ere?’… Could that be… West Country? ‘Babs is everyfin’ to us, ya see - a sister, an auntie, a niece, a muvver, a bruvver’… Hang about! That’s London, innit! ‘MY brothERS LoSe aLL sELf-coNTRol whEn tHeY vArDa SomeTHINGg ZhooSHy’… That’s… okay, that’s… wait, what is that? That was Jules, a friendly monster with a penchant for shiny - in Jules’ words ‘zhooshy’ - things. And Jules peppers every sentence with a bevy of weird slang terms. Some of them are familiar: ‘ogle’, ‘mince’, ’naff’. Some of them are novel: ‘ajax’, ‘meshigener’, ‘varda’. And rather than making things clearer, each new word only deepens the mystery. No matter how hard I squinted, I had absolutely no clue what dialect Jules was speaking or sometimes even what Jules was saying. So I did a little research. As it turns out, Jules speaks something called ‘Polari’. And if you find it hard to follow, that’s very much intended. Polari is what’s known as a ‘cant slang’ or a secret dialect. You use it when you don’t want to be understood. Polari had its harlequin origins as a language of buskers, sailors, merchants and showmen - itinerant wanderers who lived on the fringes of society. It borrows words from Italian, Yiddish and Romani then mixes them together with a generous dollop of Cockney rhyming slang. Polari was used in Britain in the 1950s, 60s and before to allow LGBTQ people, most often gay or bisexual men, to communicate in secret. But why did they need to? Well, the language of love is tricky at the best of times and is often just a teensy bit coded. People have dreamed up all sorts of delicate ways to ask indelicate questions. However, for gay people before 1967, there was much more at stake than simple indelicacy. Just 53 years ago, homosexuality was illegal in the UK and if ‘Jennifer justice’ a.k.a. ’the orderly daughters’ a.k.a. the police found out, you risked ridicule, jail time or worse. So people got smart. They used Polari as a cipher to bamboozle police, outwit informants and talk freely, even in public. As well as a code, Polari was a secret handshake. Slipping a Polari word into a sentence and watching for a glint of recognition was a safe way of knowing if someone else was also gay, or at least an ally. And beyond simply facilitating communication, Polari was a language of fun, of gossip, of freedom, hope and self-expression in the face of tyranny. Polari was full of wry jokes, acid ironies and sing-song rhymes. People adopted new Polari names and identities. For those in the know, well-spoken Polari could even be a form of theatre, and people had showmanly arguments where they’d one-up each other with more and more complex Polari sentences. Polari did not last forever. By the mid-sixties, people began to catch on. Gladly, when homosexuality became legal in 1967, it was no longer needed. However, as a sad consequence, it stopped being spoken. Of course, Polari’s legacy is still felt, and it bequeathed us several words including ‘mince’, ’naff’ and maybe ‘blag’. Moreover, there have been many excellent attempts to preserve the dialect, including Polari dictionaries, short films, and even a Polari bible translation. Even so, most people have never heard of Polari. It risks being forgotten and relegated to the footnotes of history. And without Dragon Quest Builders 2, I’d probably never have heard of it myself. This is why good localisation is priceless. Anyone who has read Asterix or played Ace Attorney or Animal Crossing will know that a good translation can breathe new life into an experience. It can recreate the ‘feel’ of the original script or a story, rather than just the literal meaning. But more than that, good localisation can add things that weren’t even in the source material. The Japanese version of Jules certainly did not speak a half-forgotten British secret slang. And it is laudable that the translators used this minor character to teach us about a vital, often painful, but nonetheless important part of British linguistic heritage. Because you can bet that massive franchises like the Dragon Quest series have a larger audience than the small group of linguists and cultural historians fighting to preserve Polari’s legacy. And it’s a wonderful thing when big media companies use their powers for good. That’s why you should go and have a dolly old varda at Dragon Quest Builders 2. Beyond the fact it’s a great game in any language, translations like this are far too rare. So get off your corybungus, buckle your batts and blag Builders 2 today, because it’s bona as heck, zhooshy to boot and fantabulosa into the bargain!