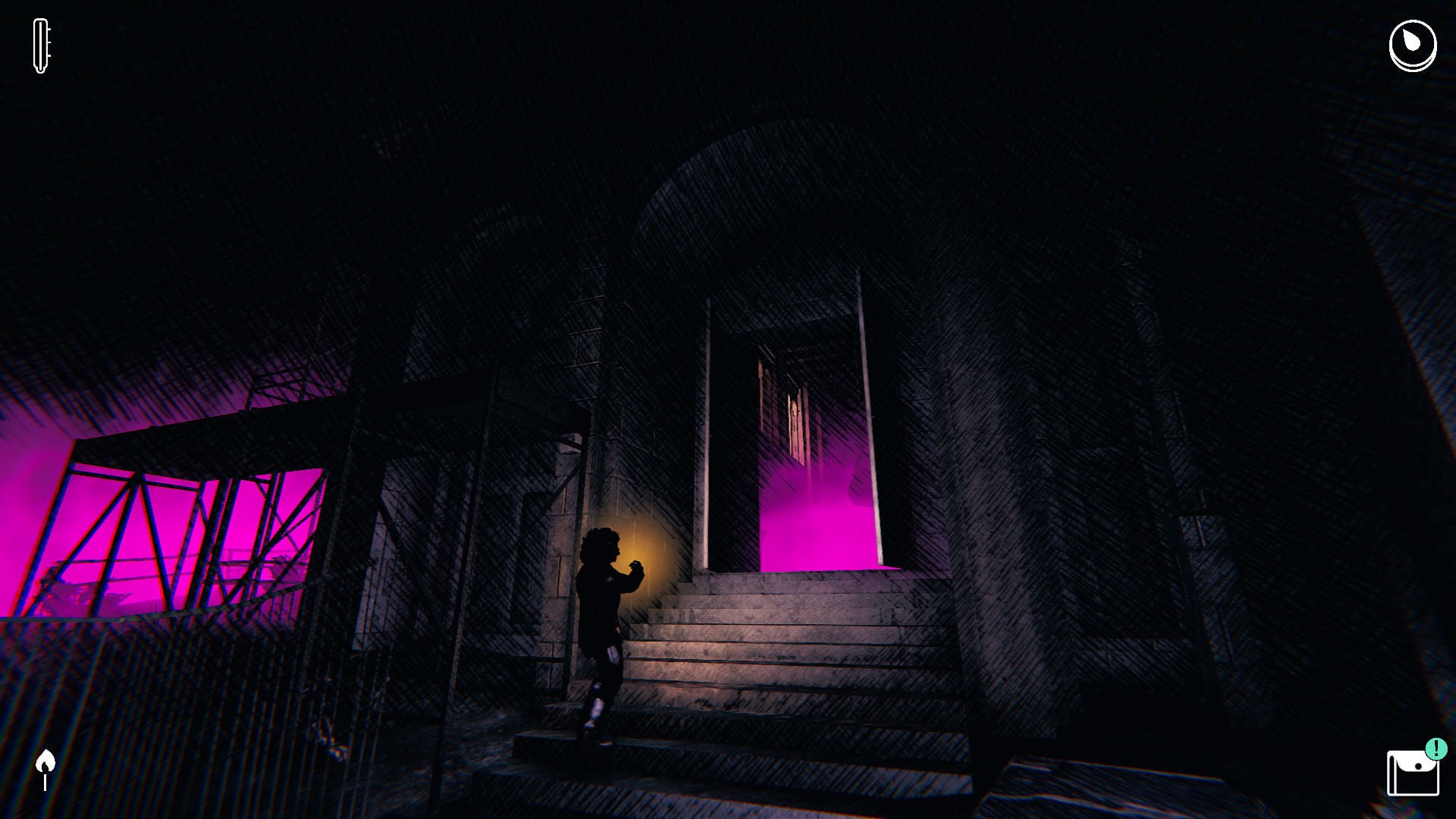

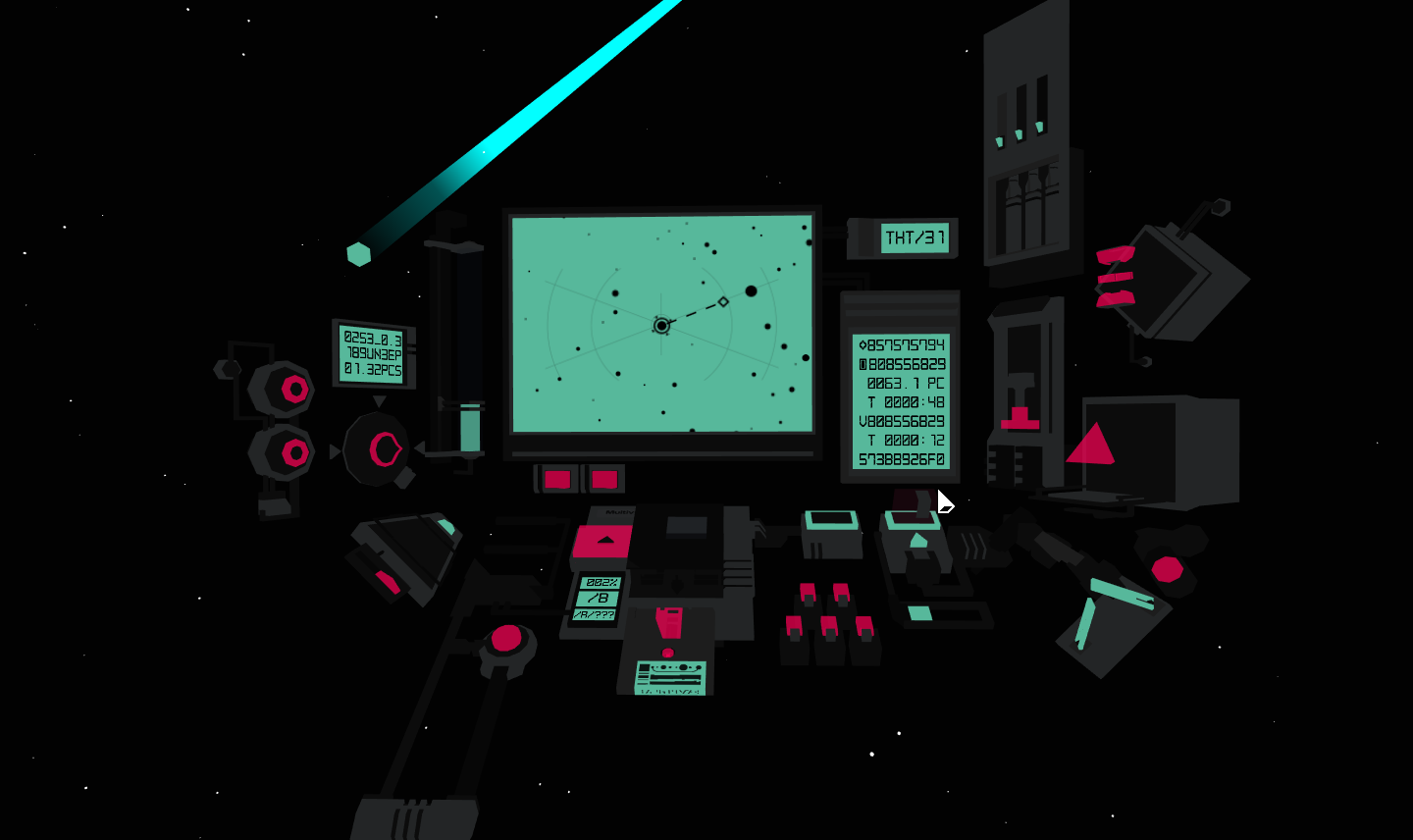

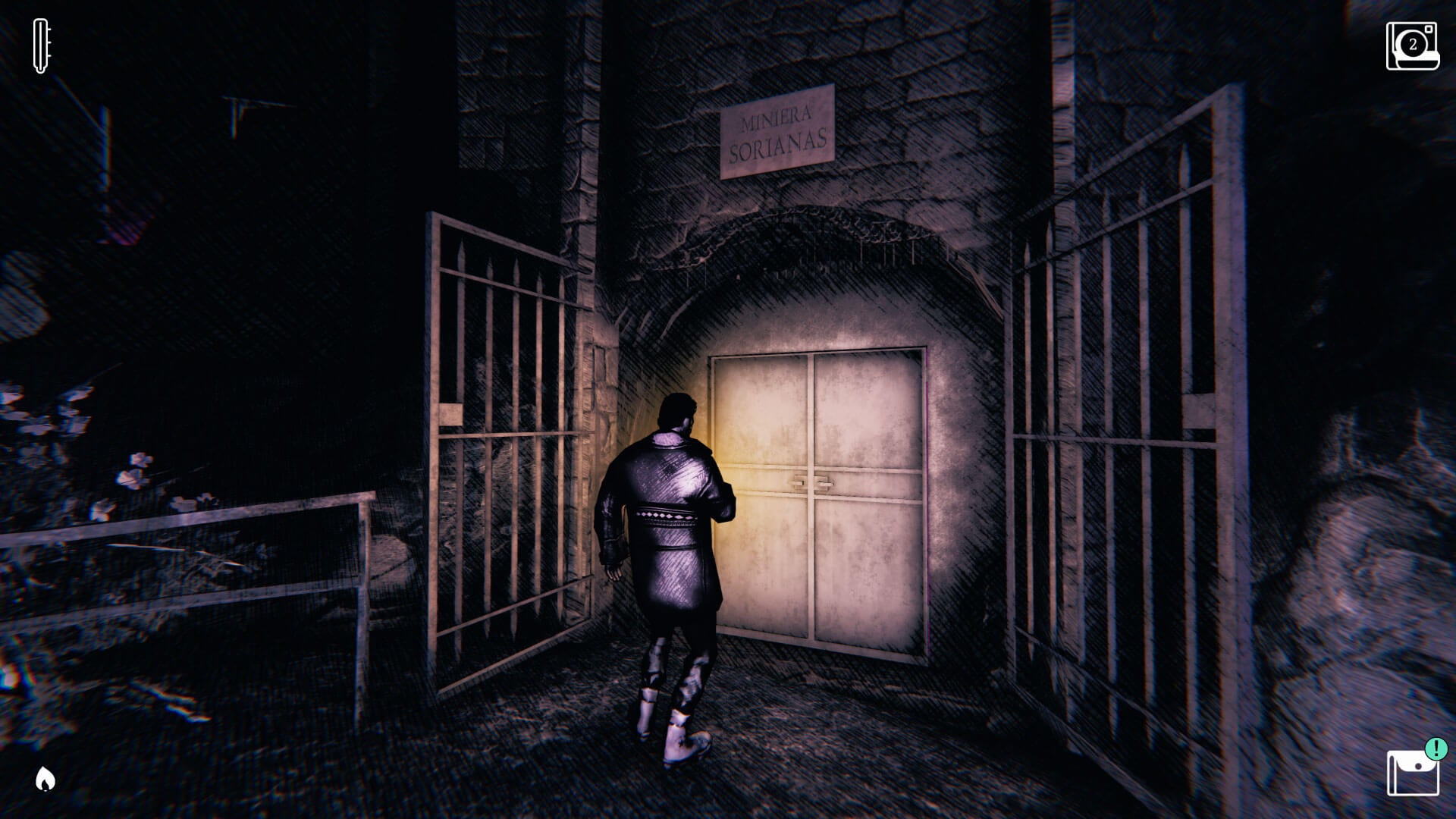

Saturnalia is the latest game from the Italian micro-studio Santa Ragione, the people behind some of the most vibrant and fascinating and engrossing games I have ever played. These people make games that create obsessions in their players, and, actually, now I mention it, you can see that a little as the town reshuffles. Saturnalia is a game about exploring a small Sardinian town after dark, hurriedly pursuing your own tangle of agendas while being stalked by something awful and unstoppable and single-minded. You play one member of your gang after another, and when they’re all captured by the stalker, the town, well, reshuffles. This reshuffling is brilliant to watch. And again it makes me think: honestly, how should I begin when I’m telling someone about this game? Sometimes the houses and streets move around as if they’re brass fixtures set into grooves. It’s a puzzle box, an orrery. I want to talk about how the game has been made with help from a physical board game company, and how the shuffling makes you see some of that physicality, the way that it’s all legit, no cheating, the way that it’s a mechanism, and the way that this allows the player to understand that the pieces of the town haven’t been added to or subtracted from - they’re just in different places. Sometimes the houses and streets move back and forth, almost mirroring each other, like those fancy dances characters are always doing in Jane Austen novels. I want to talk about how different this feeling is from MirrorMoon EP, another beloved Santa Ragione joint, and how each of this outfit’s games are a bit like that other deeply Italian source of restless experimentation, the novels of Italo Calvino. Each Calvino novel its own world with its own rules, its own modes of being. Very Santa Ragione, that - even though, when I mention this in my developer interview, I am sternly told it’s an “absolutely disproportionate” compliment. Then there’s that interview. The transcription AI service I use to write up my interview with Pietro Righi Riva, the studio director at Santa Ragione and a crucial force behind Saturnalia, has a very specific problem. A problematic problem. It can identify every word used except the word ‘saturnalia’. Time and again, the word comes up in conversation and the AI takes the wildest of guesses. After a while I start keeping a list of these paracuses, each one, somehow, an ice floe unto itself, distinct and bright. Each one a piece of natural poetry. Southern Nigeria. Sacred knowledge. Salted Melia. Such another. Such another! It’s almost too neat. And the walls move again. So let’s start in the town, its narrow paths converging, confounding, the locations of its scattered landmarks hard to fix in the mind even when they aren’t moving around. This Sardinian mining town is the star of Saturnalia, and what a star. Both maze and prison courtyard, its ageless grey walls smooth one second and fidgety with crosshatching the next, its limited viewpoints disappearing into darkness or clouds of disco fog. Bonfire sparks fill the air and sizzle over the soundtrack, mixing with cultist’s dull chanting. This town is a thing of graphite and matchsticks. When it gets dark, you have to light matchsticks to see by, in fact, each one a risk because your stock of matchsticks is limited and precious, and because maybe the light, like any noise you might make, will bring the thing that stalks you closer to your position. You play as a group of people each with their own agendas. Anita is a geologist studying the local mines. Paul is a photojournalist tracking down his birth parents. That’s for starters. One by one you venture out into the streets. Let’s see what Anita’s motive is for the moment: she wants to meet a friend at the church. But the church is hard to get into. The friend is in the belfry, but the path is cluttered and some of the areas she needs to pass through are alarmed. The first time I came here, as Anita, I didn’t even get to trigger the alarm. I didn’t get that far. My pursuer, masked and numinous, with a horrifying rattling sound that betrays their presence, was upon me long before that. Over to Paul. Paul hears Anita’s scream and decides to go look for her. (Interesting that. Saturnalia is a dance of information - at times we know much more than the characters we play as. At times they know much more than we do. Difficult!) Out we go into the town. But I know Paul is also interested in the mines - his birth father may have been a miner? It’s hard to keep track of it all. So down towards the mines I go. Where are the mines these days? The door must be opened, which involves various steps, all of them hazardous. I move around the town, using matchsticks I can’t really afford to use, lighting scattered bonfires on street corners, picking up useful items - a wrench here, camera film over there. And then I’m into the mines, searching for my father’s locker. They hang miner’s lockers from the ceiling in Sardinia. I have never seen anything like it. I need to remember the name my father was using as a miner to see which locker is his, and then I need to lower it. And of course lowering the locker makes noise, and there’s that rattling again. When I first played Saturnalia, I was in love with the Calvino Theory of Santa Ragione. In other words, all of the studio’s games are wilfully different, each rebuilding the film camera from scratch, as it were, and establishing unique rules and grammar. MirrorMoon EP - which I urge you to play, it is breathtakingly good - is a space game that drops you into the cockpit of a spaceship and asks you to learn how to fly it. That’s just the first challenge, and it’s completely overwhelming. So many switches and levers! But you prod and you poke and you flip this and twist that. The game yields to playfulness. You can learn to fly this thing, but you must first learn how to learn. Saturnalia, compared to that, is very different. At first it seems simpler: this is survival horror, right? Then the town scrambles and I lose my items but retain my characters’ threads of inquiry and I realise - oh it’s also a roguelite, though one that’s unlike any other roguelite I’ve ever played. Then I see the clues screen, and I realise - oh, somehow we’re back in MirrorMoon territory. Sort of. The clues screen is the point I fell in love. To keep track of the various scarlet threads of Saturnalia - the desires and fears of its cast, the items needed for this or that - there’s a whole screen that maps everything out. It looks like a subway map for the multiverse - lines over lines, some intersecting, some merely co-existing. Together with the mission system, a set of loose objectives that guide your characters from one moment to the next, this is how you orient yourself in Saturnalia. But I look at it for the first time and I am back at the dashboard of the MirrorMoon EP spaceship. I am overwhelmed but intoxicated. I know that to learn what to do I must first learn how to learn. Again. It turns out that this is a topic that comes up again and again when talking to Righi Riva. It came up when we talked about the scrambling of the town, and how the player needs to understand the physical rules that govern a digital space, and how the designer must first understand that physical rules must sometimes govern a digital space in order for a player to understand anything. It comes up when we do the how-are-you-with-Covid chat at the start of the call and Righi Riva explains about the coloured zone system that Italy has adopted. “Our region was shifted to the yellow zone last week, which means that we can dine in and go to a restaurant again. Which is great,” he tells me. “That only happens until 6pm. After 6pm you can go to shops, but you can’t go to restaurants. And until 10pm when you can’t leave your house at all. Except if you’re going back to your own house. It’s a bit confusing when the rules change. It feels like a game really. And the result of it is that it’s very stressful. It’s very tiring. And also it really makes you think about how we get used to situations that would be unthinkable right?” Anyway, though: Saturnalia! “You have the theme of orienteering and finding your way in MirrorMoon in a way that is very deliberate,” Righi Riva tells me. “Because you can look around you and you have this map. And that’s also in Saturnalia, the theme of like: how do I make finding your way and exploring a place a mechanic? And how do I not turn to established gaming conventions to do the same thing, right?” That’s what unites the games, I suddenly understand. How do I do this thing that other games do, but how do I make it new? Or, to put it like Righi Riva, “How do I do this without reusing mindlessly a gaming convention already exists?” Well? He laughs. “You end up with pretty weird, self-contained games that look like they’re made by people that have never played a video game in their life.” We’re back to Calvino aren’t we? “I don’t want to speak for Calvino, of course,” says Righi Riva, “But I think when you when you’re approaching something, in that sort of playful, experimental way, where you’re like: hey, I wonder if I can write a book by using a deck of cards? Inevitably you end up with something that is inevitably a little weird and all different from everything else you’ve done, just because it starts from a very different premise. But it probably shares with the rest of the things you do that same approach to playful experimentation of, like, finding different ways to achieve something.” This is clearly something Righi Riva has thought about a lot: why Santa Ragione’s games end up as the kind of fascinating puzzle objects that they are. “I can’t compete with, you know, people that have like that super deep knowledge in a particular genre in games and that can create the perfect Metroidvania,” he says. “And I don’t think I have it in me that I can make a ‘gamey game’ that is better than anyone’s, or everyone’s? But what I think I can achieve is trying new things in ways that something is left that others can reuse, and start from. Like, can we make this? Let’s give it a try? It’s got to be a starting point for trying to do things in a slightly different way. And I think that’s our role and what we can do with the size that we have, with the budgets that we have, the sensibilities we have.” Often, what the team is doing is balancing real things with abstract things - physical things and then digital things, the mystery before the players in Saturnalia and the freewheeling tangle of the clue screen. “The idea is that interesting situations emerge from coherent real systems,” Righi Riva tells me. “And they emerge from observing those.” Example? They talked a lot when they were making MirrorMoon about how much fun it is to play with a broken radio. “As kids, if you’re a kid, and you find a broken radio, and you start pulling the levers and switching the knobs, the game’s already there. Because there is this physical coherence between the things that you touch, that has some feeling, some meanings, it evokes stuff, and then you fill in the rest of the fiction with your mind as a kid. “The important part is that this physical thing has its own rules,” Righi Riva adds. “That you don’t necessarily know but that you feel these rules are there or imagine that they’re there. And it’s much easier to trigger that feeling if there is actually a system connecting this stuff.” This gets at a crucial feeling I have when I play all of Santa Ragione’s games. I feel that they have so much trust in the player. Dumping them into that terrifying cockpit. Letting them loose in a strange town with nothing but matchsticks. Actually, more than trust, it’s a confidence: this team are confident that the player can put everything together. “Ahhhh that’s not necessarily a confidence,” laughs Righi Riva. “It’s the feeling of trying to achieve what I know I feel as a player, that sense of discovery and understanding things and learning to do things on my own from observing and experimenting within the game. This is the feeling that I want other people to feel. And in that sense, it’s almost more than confidence. The way he describes it, in fact, it’s almost a form of triage. “It’s like: some people will get it and some people won’t.” He laughs. “And that’s fine, because the only way to do this is by accepting this limit, that not everyone is going to go through this.” A pause. He wavers. “You know, I’m super conflicted about this, because there is an argument there where you would say: but what about accessibility, right? Like, why are you deciding that some people can’t play your game? But…if you’re not willing to engage in a certain way with the game, you will not be able to experience this one thing that we’re trying to make you experience. And if we make it easier to achieve, you will not experience it in any way at all. I suffer when I think about it, I’m not happy. I wish that this could be done for everyone.” Actually, this is a central part of how Saturnalia has been put together. “That’s definitely been a guidance in the design of Saturnalia,” Righi Riva says. “Where we use a constant process these last three and a half years, finding mechanics that you need to learn, and need to understand how they interact with each other. And, then we go through it all thinking, how can we make this more accessible, but in a way that people don’t feel guided?” This is hard work. And there is no single solution. Sometimes it’s the mission system, which literally gives you a prompt to try and solve a specific problem with the character you have before you at any given moment: Investigate the mines! What happened to Anita? Sometimes, it’s a character turning their head at something and noticing it - something that you might not necessarily have seen. The mission system was not in the game from the start, and I can tell Righi Riva is still somewhat conflicted by it. “So the first version of Saturnalia, we played for a long time and we did not have the mission system, right?” he tells me. “The game would never tell you what to do next, you would have to infer it from the stuff that you find, right? And it was much more investigative, an investigative game.” Actually, they are considering adding this way of playing back in before release, as an optional mode. “I like it because it makes the game almost completely unplayable,” Righi Riva laughs. “But if you go somewhere in the game, without anyone telling you and you notice that door, you notice that house, you go inside, and you find something just because of everything that you learned up to that point, it’s so satisfying.” He sounds almost mournful. “But you know, you have to strike a balance between making the game extremely satisfying for those that want to invest a lot in it and making it accessible for everyone else that is used to a certain kind of guidance inside games.” Righi Riva knows that this feeling of discovery, creating that feeling, is a real strength of the studio. “So it really went out of fashion, I think, at the beginning and mid-2000s, to make games that weren’t guiding the players a lot,” he says. “It used to be more common, like King’s Field or something. And for a variety of reasons. One was terrible translation, or limited technological capabilities. But then, that kind of Nintendo way of making games that guide the player no matter what, and that make everybody clear, contaminated everything. And on the other end, you had this new wave of triple-A games. Movie-like experiences where you would have very little friction into progressing.” He stops to listen to himself. “Which is something I like!” he adds, laughing. “Some of my favourite games are triple-A games!” But that word choice: contaminated. “Now I don’t think it’s that exceptional what we’re doing in these terms. Except we apply it differently. I think the new thing we do is that we apply this idea to systems that are otherwise considered established, right? Like the finding-your-next-objective kind of thing. It’s hard to make those maps and those markers and the procedural diegetic signs that work in the 3D world. And sometimes I feel like, can we just show the marker where you have to go next? And it’s: no! You can’t. We mustn’t.” Because of this process, Saturnalia has a load of moments where it feels like the team has hit a lovely sweet spot. Take orientation. If you find a map of the town, your character can choose to memorise a specific location, which will then show up as a vague marker when you stop moving and press a button. But they won’t memorize it forever, and anyway, it points you in the right direction but it won’t really take you there. And then there’s my favourite button in the game. You press it and the character you’re playing as at the moment thinks to themselves - you get to hear their thoughts for a few seconds. What a brilliant idea. And so nickable. I tell Righi Riva that I hope other developers nick it, in fact. “I hope so too!” he laughs. As our time comes to a close, I finally ask Righi Riva about the setting of Saturnalia. I’m ignorant about Sardinia, so much of the fun of playing is seeing this culture that is new to me and trying to get a sense of it. And also wondering where fact and invention separate. Those miner’s lockers - such a great game element. That’s an invention right? Or are Sardinians playing the game and thinking, “Wow, a classic Sardinian mine locker! That sure takes me back!” “Mine lockers from the era were really made like that, suspended with chains and pulled to the ceiling,” says Righi Riva. But he adds that, if I’m ignorant about Sardinia, so was the team back at the start. “It’s by design,” he says. “We went explicitly to a world, a culture, a place that most people wouldn’t know about. And we didn’t know about it really. We knew there was something there, but we didn’t know how much.” So it was a process of discovery for the team? “It was a process of discovering things and putting them in the game,” he says. But they still had to be careful. The pursuing creature, the horror aspect of Saturnalis, is inspired by Sardinian traditions, but it’s also an original invention. “We didn’t want to steal any of the real stuff,” Righi Riva tells me. “So if you really go and look at Sardinia, with the carnival there’s lots of masks and lots of rituals and lots of mythology. But we decided not to choose one of those aspects and turn it into a horror game, because that’s not at all the meaning that they have, they all have their different things. It’s almost a religion in itself. So it would have been disrespectful to do that. That’s why it doesn’t take place in a real Sardinian village. And the horror and the creature behind this is new.” He stops and thinks. “But a lot of the stuff that is so horrific is actually real, from real life.” So in the end, you have to figure it out? The designers as well as the players? “Yeah,” he tells me. “It’s fun to figure it out.”